Reimagining Bike Parking

A human-centered design project to redesign the experience of bike parking on the UC Davis campus.

Background

The University of California, Davis is located in the small town of Davis, CA, known as the "Bicycle Capital of America". Biking is a central aspect of student life, and over 15,000 – 20,000 bicycles are used by students on the UC Davis campus every day of the week (Source).

Problem

Reimagine bike parking on the UC Davis campus.

Process

The human-centered design process is a creative approach to problem-solving that focuses on empathy for individuals to create solutions based on their needs.

Part 1: Understanding

User Research

I interviewed seven UC Davis students to learn about their experiences with on campus biking. These conversations served to help me understand the context of the problem:

What choices and actions do students make?

What are their pain points?

What are the cultural norms and expectations of bike parking on campus?

Several insights kept popping up during these interviews. Parking spots are difficult to find during peak class times, students must leave for class early to find a parking spot, and using a rack with a bike already locked to it is bike parking taboo.

However, one interviewee stood out to me: Soham, a coworker who bikes everywhere he goes. I learned that Soham is often late to class not because he can’t find parking, but because he can’t find his bike. Soham bikes to class and usually park close to his classroom, but he has a difficult time finding his bike when it’s time to move on to the next class.

At the end of the interview, I asked Soham where he was currently parked. He simply responded, “That’s a good question.”

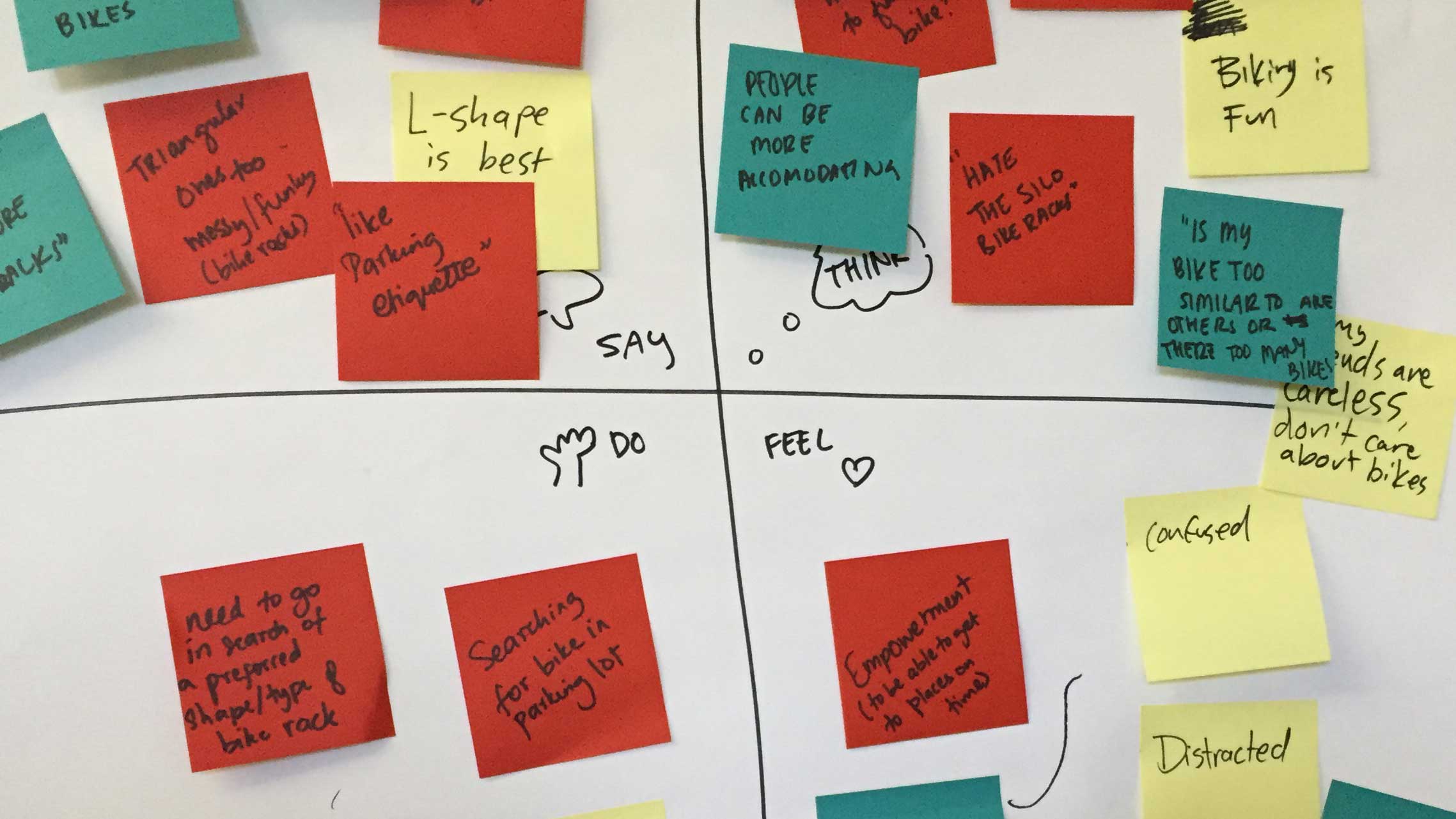

Unpacking

I used an empathy map, an exercise that forced me to take what I saw and what I heard during my interviews, and discover the meaning behind them.

I filled up the “Say” and “Do” sections with sticky notes with instances from my interviews, then translated these into what this might mean the interviewee thought and felt in the “Think” and “Feel” sections.

Framing the Problem

From my empathy map, I pulled out the feelings, overwhelmed, embarrassed, disorganized and rushed. With these feelings in mind, I drafted a metaphor to help others and myself better understand Soham. I aimed to convey the emotions of being completely overwhelmed in a densely-packed area, looking for one specific thing amongst many others that look the same.

When Soham can’t remember where he parked his bike, he feels like he is walking through an IKEA warehouse searching for an item without knowing the aisle and bin number.

I then brainstormed what the opposite of this metaphor would be, leading me to the following "game-changing" statement.

It would be game-changing to create something that makes searching for his bike feel like spotting a water tower in the distance.

Part 2: Ideation

"How Might We" Statement

The unpacking and framing exercises translated directly into a “How Might We” statement, tool to create a more specific and tangible problem to ideate solutions for, and serves as a starting point for brainstorming creative ideas.

How might we make Soham feel like searching for his bike is as easy as spotting a water tower from the distance?

Brainstorming

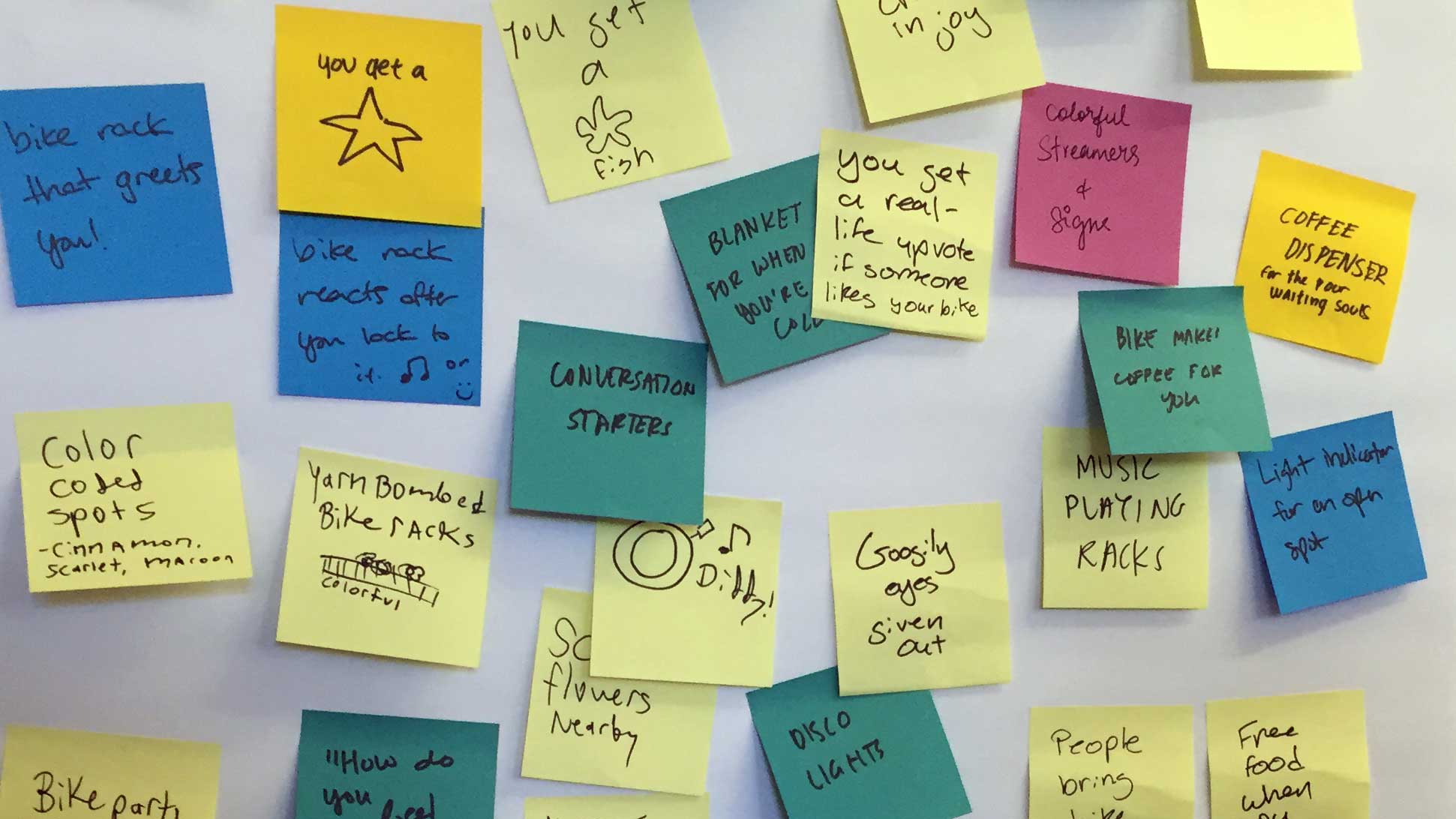

Several classmates and I responded to this “How Might We” statement in a rapid and collaborative brainstorming session, which resulted in a plethora of possible solutions to further develop.

Prototyping

I chose one idea to focus on: color-coded bike parking.

Because innovation is often interdisciplinary, I decided to connect this challenge with something I learned in a psychology class.

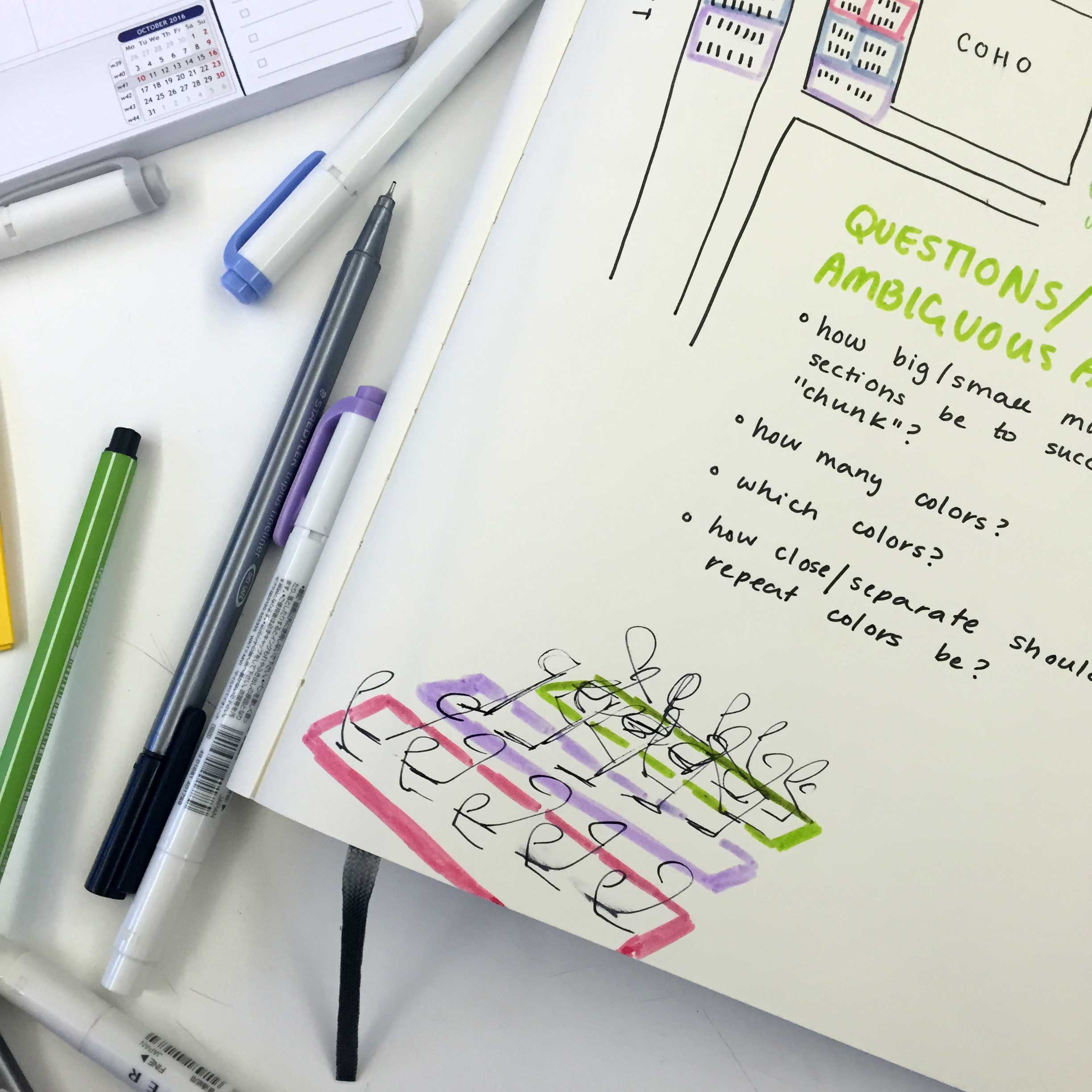

Chunking is a memory technique people use to turn large piece of information into “chunks” to help them remember more easily. When we chunk 9 digit phone number into three sections, for example, it becomes much more manageable to process and memorize.

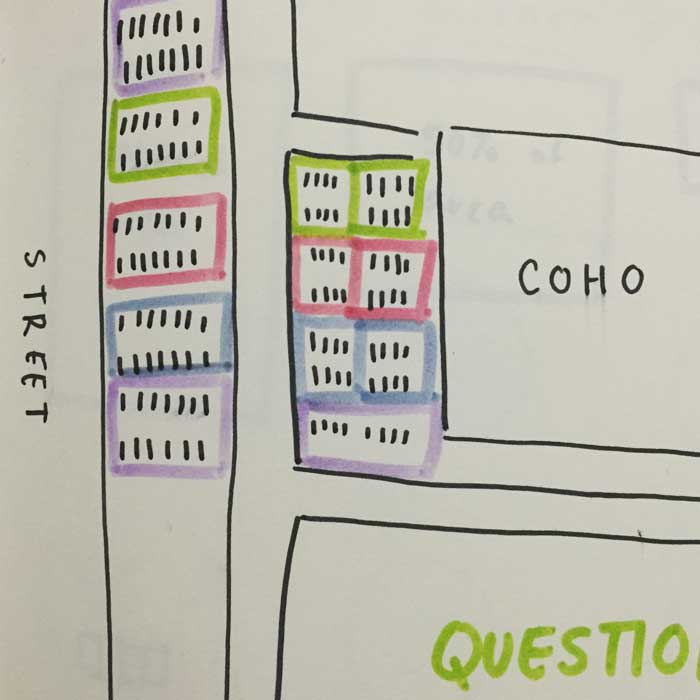

To connect color-coding and chunking to help Soham find his bike more easily, I created several drafts of a prototype that chunks sections of bike racks into smaller colored sections.

Part 3: Implementation

Testing and Feedback

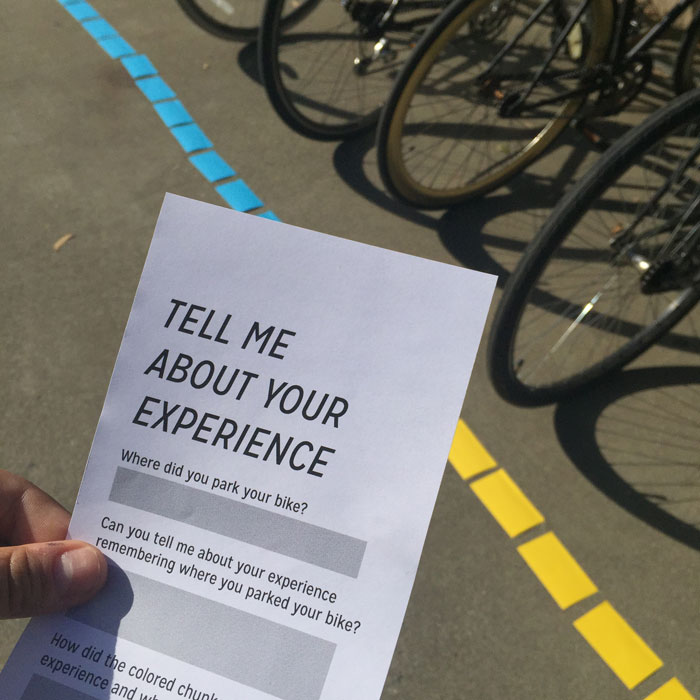

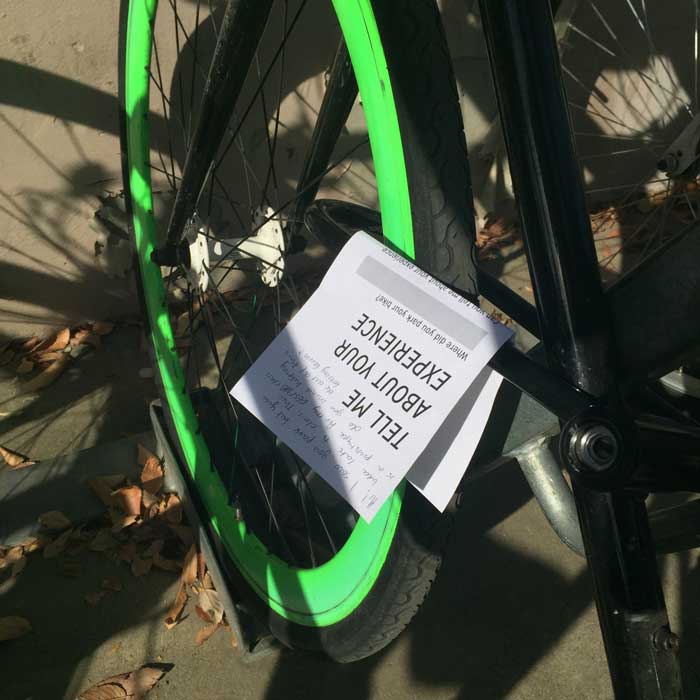

I created a low-fidelity prototype by chunking several sections of bike racks with colored post-it notes.

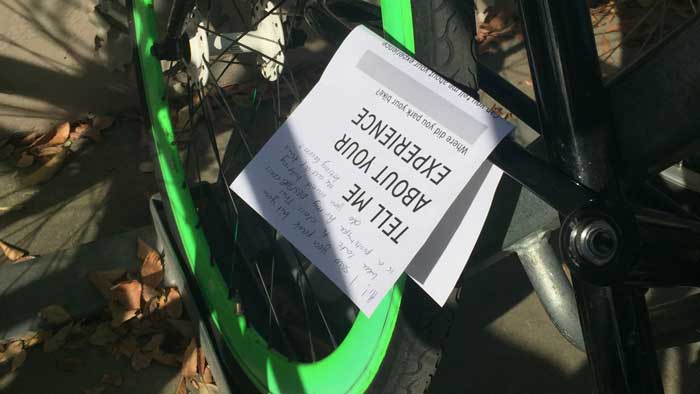

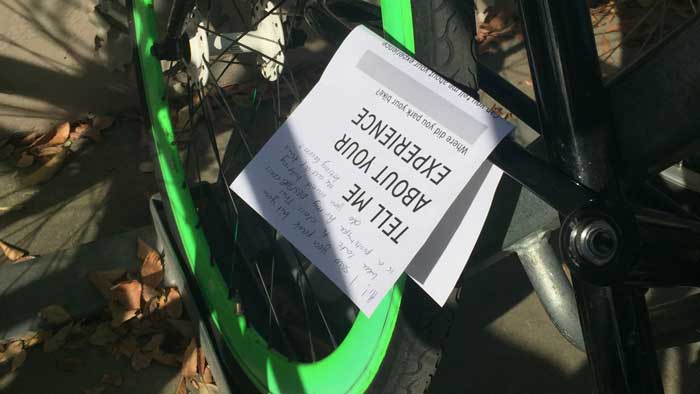

I was wary of telling the users that the purpose of the colored perimeter was to help them remember where they parked, as this had the potential to create bias in feedback. Instead, I created experience surveys that I left on the users bikes after they left. The surveys asked the users to describe their experience and to tell me where they parked, with instructions to email me the results.

Scroll table to view feedback

+

|

−

|

Changes

|

New Ideas

|

Conclusion

Though this prototype is just a beginning step to reimagining bike parking at UC Davis, the human-centered design process and empathy exercises allowed me to foster rich cultural insight into the individual experiences of UC Davis students.

UC Davis students have a lot going on. Almost all of the people I talked to were in a rush when getting their bikes, and their some didn’t consciously connect the prototype with bike parking.

This is important to consider when further developing other prototypes, and led me to predict that successful solutions to bike parking on the UC Davis campus need to be small, unnoticed changes that still make a big impact.